By CARONAE HOWELL, From the New York Times, dated July 20, 2009

I’m the kind of woman who spends entire days thinking of nothing but birds: woodcocks, goldfinches, kingfishers. I look for loons everywhere I go. Sometimes I find herons in Central Park and they are mysteries. There is one thing in this world that I envy: the hollowness of bird bones. In the three milliseconds of liftoff, a bird separates itself from its problems. The sky is the freest part of the world.

I have always been depressed, and I have always wanted to fly — not to emulate Superman or to travel faster. I want to fly because of the elation. In my dreams I am a butterfly or a fairy or a honeybee. Depression, for me, is when you want to be a bird, but can’t.

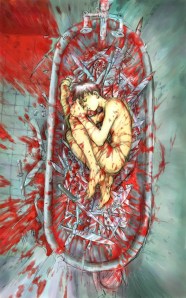

There is a specific moment in which I became a woman. It was February — always the worst month with its aching light and its slip-induced bruises. I had been trying to fall asleep for at least four hours. At 3 a.m., I found myself sobbing and shaking and confused, sitting on my metal dorm bed in the bird-with-a-broken-wing position. I dug my fingernails into my forearms, leaving shell-shaped trenches behind. I have the kind of skin that refuses to heal, just stays eternally raw and mottled. It was five weeks into my fourth semester.

In late January, a freshman hanged himself in my old dorm. I found myself asking, really, how hard is it to suddenly find yourself perched on a sink, rope around your beautiful neck, ready to fly? How hard? My dad drove through four states to pick me up the next week. On the way home I had tea and ice cream. He asked me if I remembered the time he took too many of his antidepressants. I did not. Nor did I remember my uncle’s suicide (gun to the cerebrum) or my sister’s delicately sliced arms and hips. These were things I had only been told. The space between my skull and my irises hurts sometimes — hurts like the shatter of a tiny bird that has fallen midflight.

And so it was that sour February night that I took the delicate step into the adult world: realizing that I was too depressed to stay at college was realizing I had not only lost my flock; I had fallen from the air entirely. Michigan has many birds. My favorite might be the wood duck, with its banded neck and flat little wings. When I watch birds take off, I hold my breath. They always make it to the sky.

Every Monday morning at 9 I see my therapist, mug of green tea and honey close at hand. I take new pills now. I have a routine: oatmeal in the morning, Wednesday nights with my father. I tell my therapist about Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon.” Who isn’t searching for their people? I arrange my thoughts. (No, I have never been in love and I am, in fact, afraid of men; I panic in Times Square; I grow attached to almost everyone I meet.) I have feathers and questions.

I moved to New York City for college in 2007. School did not grow me into an adult, nor did voting for the first time or doing my own banking. These things were not confrontations. How did I arrive at the place where I could look at my disease and say, “Yes, you are here, but I will not let you take the joy out of looking for birds”? I like to think it was New York, or my newfound discipline, but it was a more internal revolution. I acknowledged my traumas: I was not crazy, just damaged. I was molting. Columbia gave me many new things: a copy of the “Iliad” with a note saying the first six books should be read before orientation, a job in the oral history office, a sense of time management.

But without my sanity — without joy — these things had little value. I knew nothing until I knew I was hardly living. Hobbes and Locke and all the philosophers in the world could not matter when each day was insurmountable and burning. In my year and a half at Columbia, I began to learn how to love myself. I tell my therapist about my earliest memories and the bizarre geography of my family. I’m anxious and I have no self-esteem. But I am mending. Fifteen lost credits is a small price to pay for happiness. Perhaps I am learning how to fly. My bones may not be hollow, and joy will never come easily, but the beauty is in the struggle. The birds are everywhere.

Caronae Howell, Columbia, class of 2011, history major